Miracle on Ice still stands the test of time

A hockey game at the Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, N.Y. has taken on mythical proportions and still resonates as the ultimate underdog triumph.

Forty-five years ago today, while reporting for Newsday at the Lake Placid Olympics, I covered a hockey game.

You might have heard or read about it. You might even have seen a movie about it. Or two.

The opponents were the mighty Soviets, so precise and disciplined and dominant in their Big Red Machine era, and coach Herb Brooks’ underdog U.S. team, which had blazed through the preliminary round of the Olympic hockey tournament fueled by their young legs and work ethic and the unity players had formed against bad-cop Brooks’ deliberate dictator tactics.

The consensus was that the Americans, who had been crushed by the Soviets 10-3 in a pre-Olympic exhibition game at Madison Square Garden less than two weeks earlier, could hope to be competitive at Lake Placid and maybe win a bronze medal. Maybe. And then only if everything went right.

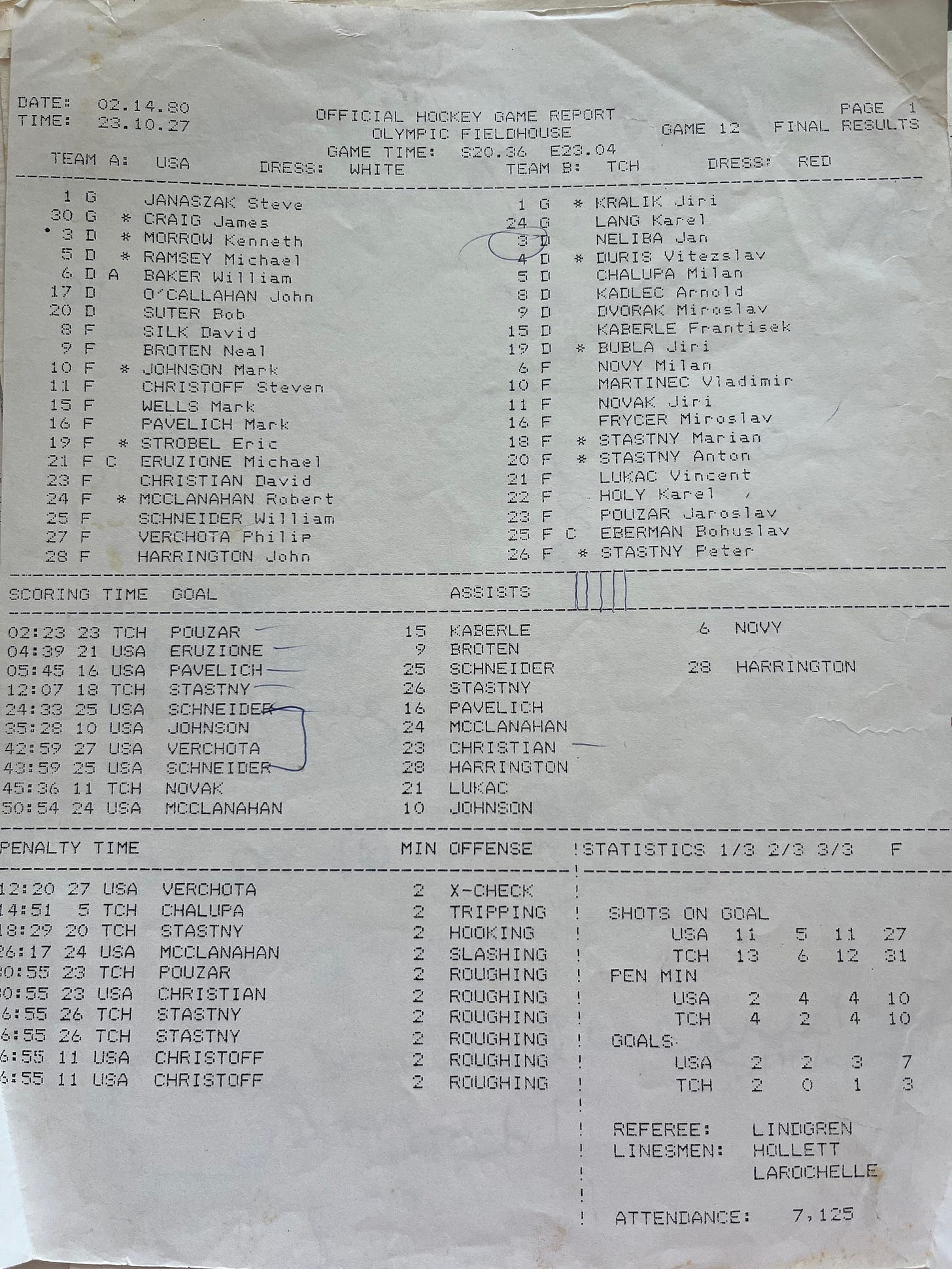

My boss at Newsday, the late Dick Sandler, had assigned me to cover the figure skating competition at Lake Placid and to cover hockey until the Americans were eliminated, he said. But the Americans refused to be eliminated, tying Sweden in their opener and following that with a rout of a star-studded Czech team in their second game. (Note all three Stastny brothers on the roster, as well as others who later played in the NHL)

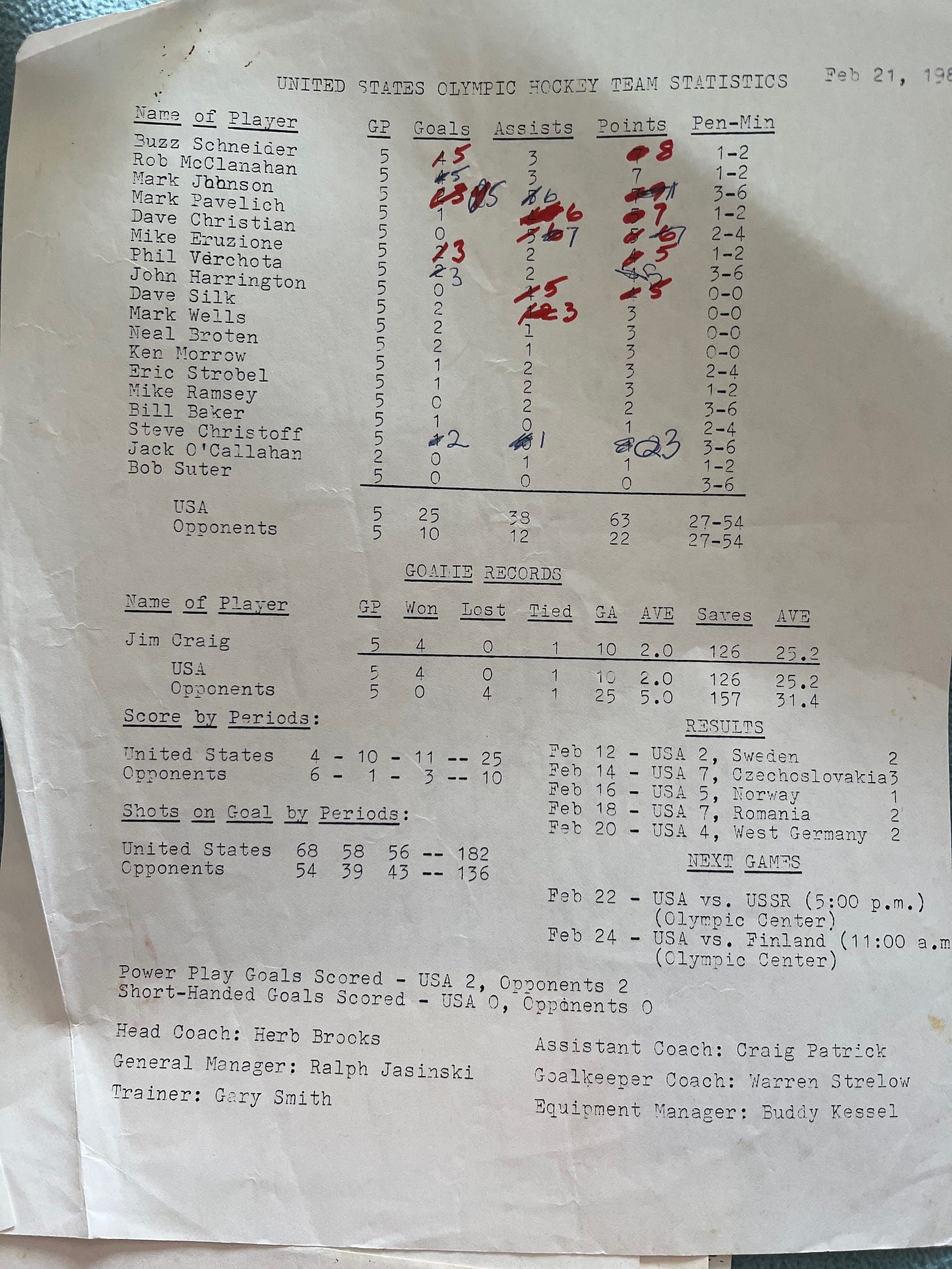

The road to the medal round was surprisingly easy. And note the Americans’ scoring margin in the third period of their first five games, reflecting the youth and conditioning of a team almost entirely built around college kids. Brooks had pushed them, sometimes mercilessly, but he knew that “the legs feed the wolf,” as he told them.

The question I’m most often asked when I mention that I covered the Lake Placid Olympics is whether those of us on site knew how big a deal the U.S. hockey team’s success had become not only in the U.S. but around the world. Remember, this was the pre-internet era, before 24-hour cable news and the ability to pick up your cell phone and check breaking news on web sites. Back then, Lake Placid was a small, isolated mountain town, tucked away from the bigger world, so it was impossible to know how big a story it was becoming.

We had some hints that the team’s success was resonating with a greater audience: I remember getting calls from editors back at the office, telling me that readers were interested in the hockey team and asking me to write more stories (I remember writing about the “Iron Rangers” line of Buzzy Schneider, Mark Pavelich, and John Harrington, named for the region of Minnesota where they grew up. Harrington was funny, Schneider was interesting and Pavelich, bless him, was media-shy).

But the biggest indication that the world was paying attention came in the form of telegrams people were sending to congratulate and encourage the team. Someone had the idea to post those sheets of yellow paper on a wall inside the arena, making them a visible barometer of how big this had become in transcending a mere sporting event. The U.S.-Soviet matchup took on an even larger meaning because of the two nations’ political Cold War rivalry.

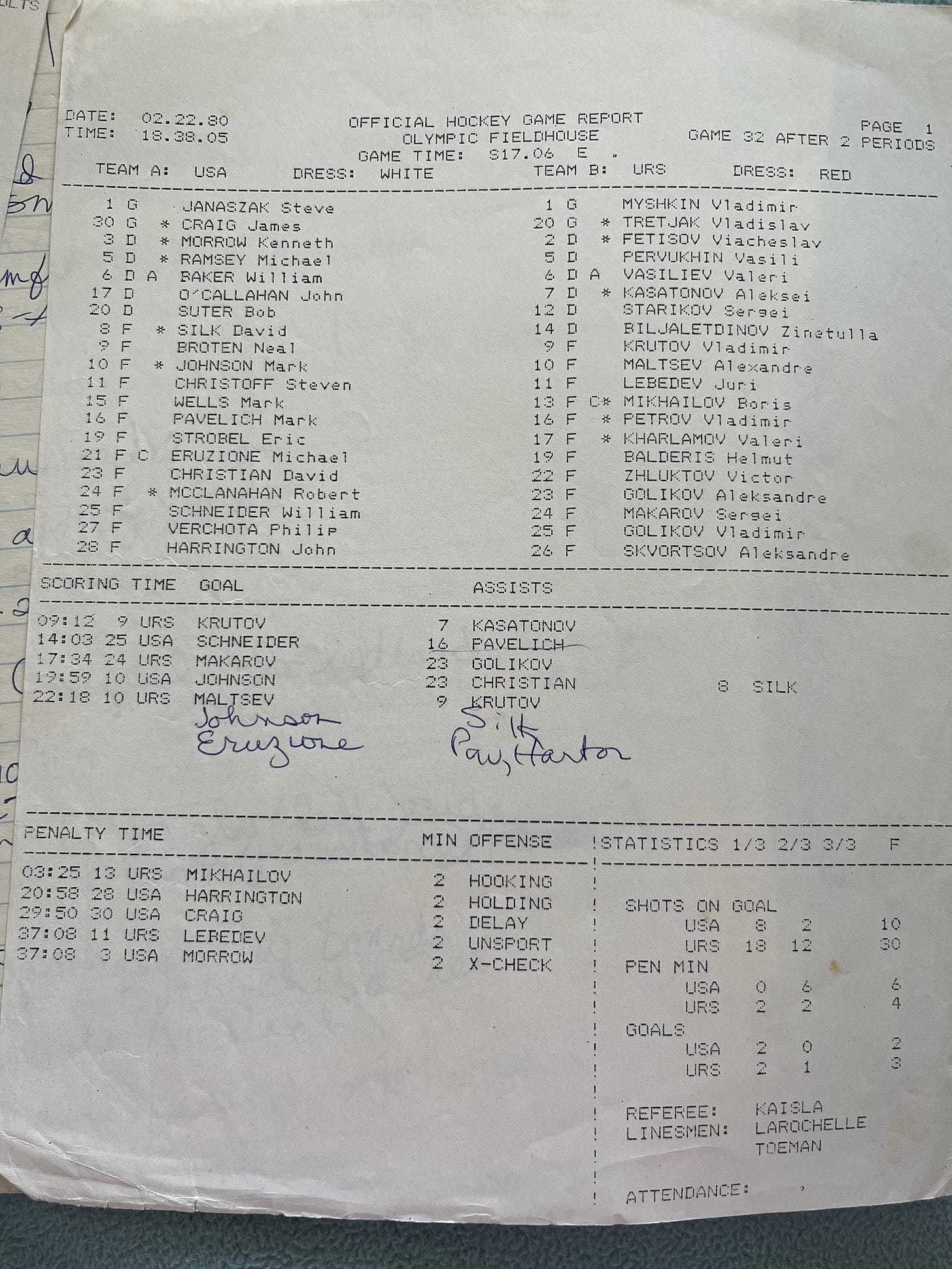

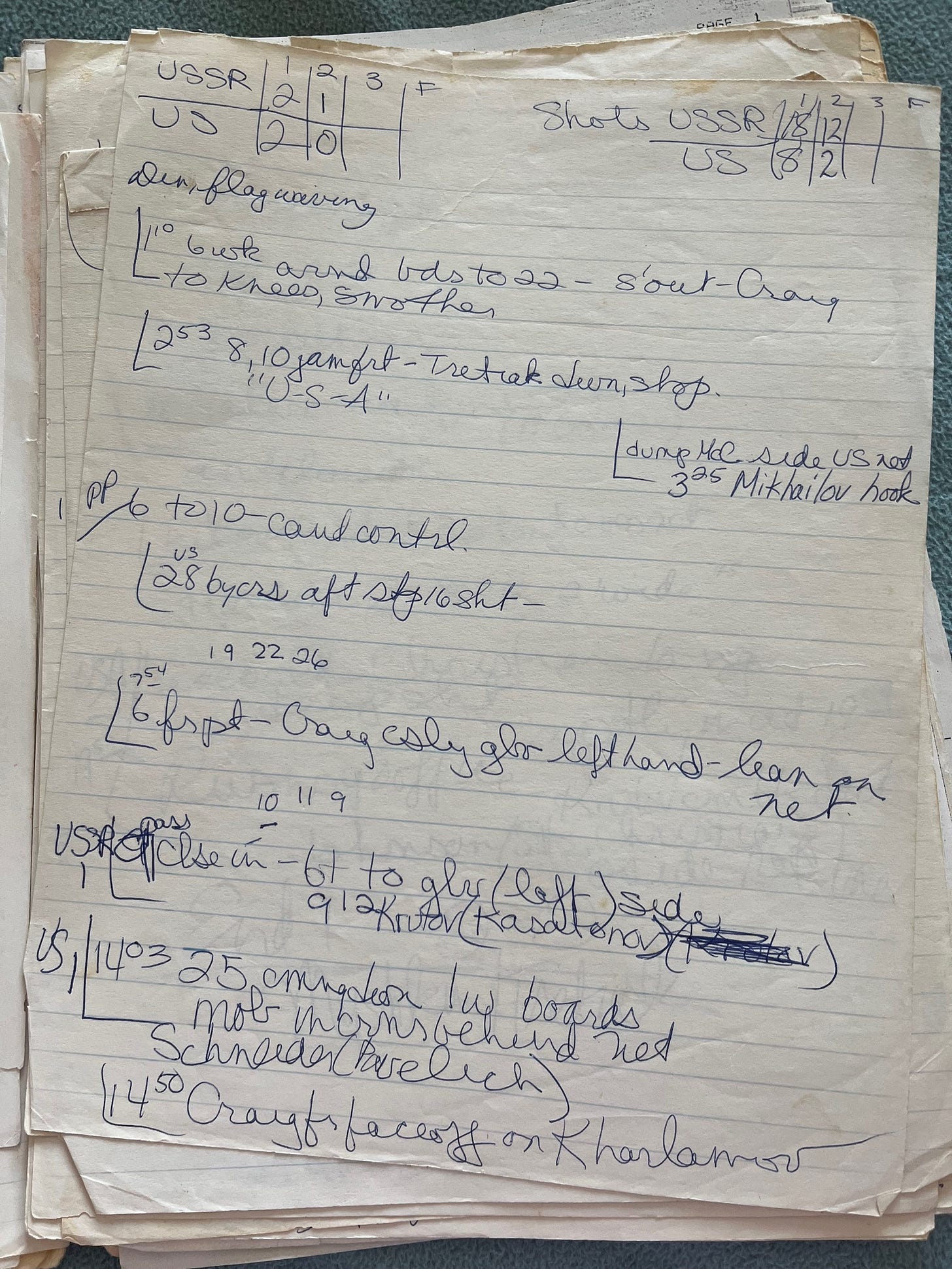

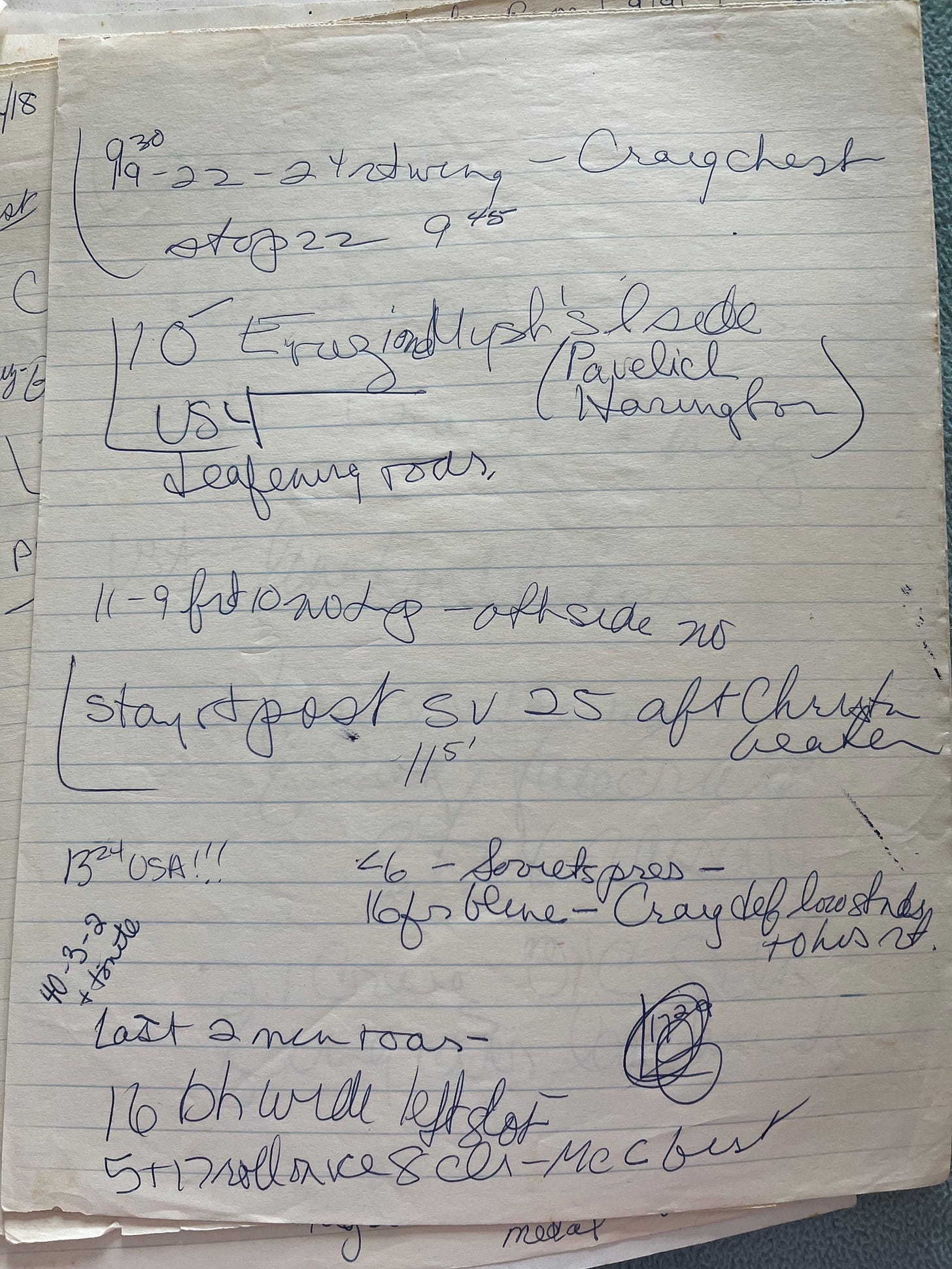

The press box in the Olympic field house was so small and the anticipation built during the Americans’ early success had grown so large before the game against the Soviets that more reporters had suddenly become interested in covering the games, which pushed other reporters to sit in the stands. These are some of my notes, probably written using my knees as my desk.

And here are my notes from later in the game:

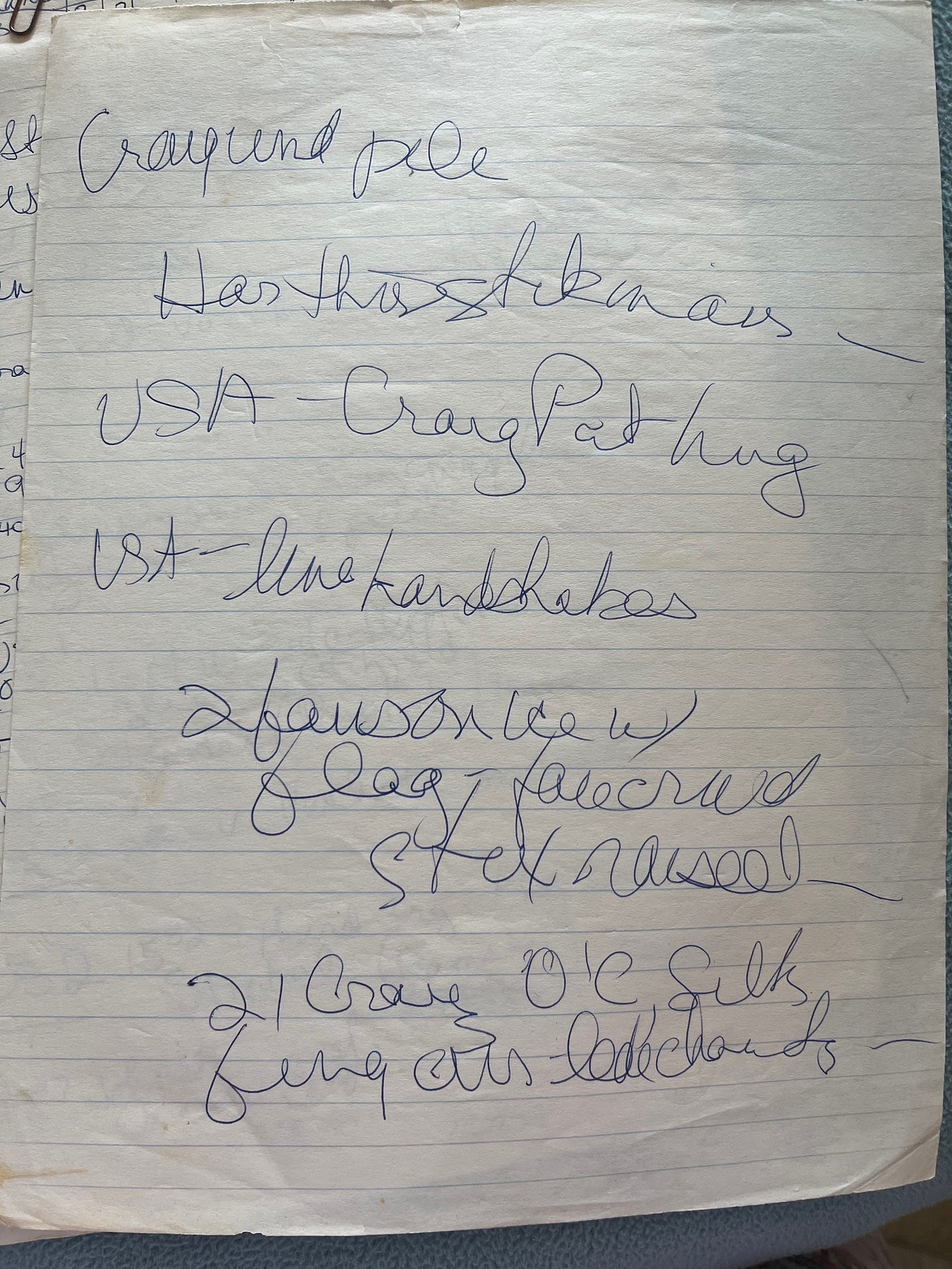

And this was what I scribbled afterward, while standing to see players rolling around on the ice. If you can’t translate my scrawls, the first line says, “Craig under pile,” meaning a bunch of his teammates had swamped him in celebration, and the second is “Harrington throws stick,” in expressing his joy. The rest were about the “USA” chants that broke out, assistant coach/assistant GM Craig Patrick hugging players, the handshake line, fans jumping on the ice with a flag, players raising their sticks to the crowd, etc.

I remember walking out of the arena after the game to see streets clogged with dancing fans shouting, “USA!” At one point I stood next to a member of the Russian delegation, who was wearing one of those big, furry hats as he watched the celebrations. When I looked at him, he smiled and held up his index finger and said, “One. You are number one.”

I described that scene in the first paragraph of my story, but an editor changed it to something about the Soviets having the team and the U.S. having the dream. Yes, I’m still bitter about that 45 years later!

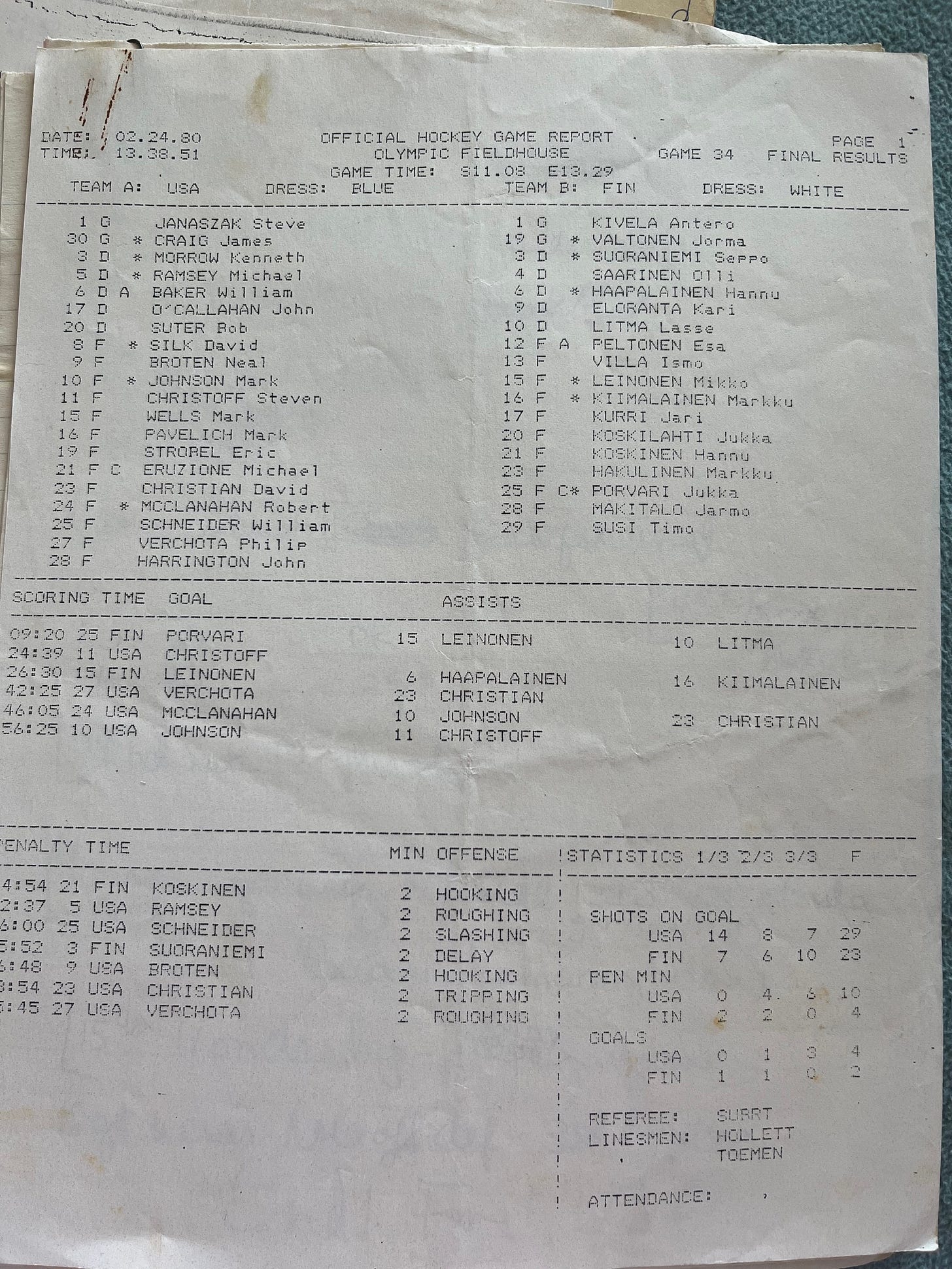

Over the decades, people have come to think the U.S. won the gold medal by beating the Soviets, but that wasn’t the case. The Americans still had to play Finland two days later, a tough prospect, especially following that emotional and stunning upset. They had to rally in the third period to do it—again, using those young legs—but they pulled it off.

Many books were written and movies made about the Americans’ shocking triumph at Lake Placid. The first movie, “Miracle on Ice,” was released in 1981 with Karl Malden playing Brooks. I remember telling Herb that Malden had been cast to play him, and Brooks didn’t approve. “Isn’t he a bit old?” Brooks said, archly, but with reason. Brooks was 42 during the Lake Placid Games; Malden turned 69 the year the movie was released.

The second movie, “Miracle,” was released in 2004 and featured an almost eerie performance by Kurt Russell as Brooks, complete with Brooks’ mannerisms and trademark plaid slacks.

Many of the U.S. players went on to the NHL, with a few enjoying outstanding careers. Defenseman Ken Morrow transitioned nicely from a gold-medal triumph to the first of four straight Stanley Cup championships with the New York Islanders; Mike Ramsey became a premier shot-blocking defenseman who played more than 1,000 NHL games, mostly notably for the Buffalo Sabres. Neal Broten won the Stanley Cup with New Jersey in 1995 and played nearly 1,100 NHL games. Dave Christian, who was moved from forward to defense shortly before the Olympics, also topped 1,000 games over a 15-year NHL career.

Mark Johnson (669 games over 11 NHL seasons) and Pavelich (335 games over seven NHL seasons) were wizards with the puck, but they were small and were battered in the physical NHL game. Goaltender Jim Craig, so exceptional in the upset of the Soviets, played 30 NHL games over three seasons but couldn’t recapture that level of success.

I’ve always thought that team captain Mike Eruzione, who scored the winner against the Soviets, was smart for not trying to play professional hockey. He knew it would be impossible to top that gold medal victory, and he has had a fine career as a popular motivational speaker. He addressed the U.S. team before last week’s 4 Nations Face-Off finale, keeping that miracle memory and spirit alive for another generation.

The kids of 1980 are in their 60s and 70s now. Since then, the team lost defenseman Bob Suter to a heart attack and lost Brooks (who returned to Olympic coaching in 2002) to a car accident in 2003. Pavlelich, a troubled soul, took his own life in 2021. The surviving players and staff occasionally meet at reunions, where the Olympic stories flow.

At some point, I’ll donate all these wonderful rosters and game charts and Lake Placid media guides to a museum. It was impossible to imagine, back then, that a hockey game would become legendary and would be so cherished a memory 45 years later—and beyond.

love seeing the hand-written notes!

Like most people I remember where I was when they won. The radio was on at my job and an announcer interrupted the music with the announcement. I was shocked. I had watched the 10-3 game a few weeks earlier and didn’t see anything in that game that left me with hope. Sadly I just read the 2022 article from the Athletic on Pavelich and his suicide by Dan Robson. It’s an article everyone should go back and read. Thanks for a wonderful article Helene!